What will the cities of the future look like?

27 May 2022

With the global population set to peak at 11 billion people by the end of the century, policy makers are thinking hard about the way cities develop. But what will this mean for the construction industry? Lucy Barnard reports.

Oceanix Busan will start with three platforms housing 12,000 people but could grow to more than 20 platforms. Picture: Oceanix

Oceanix Busan will start with three platforms housing 12,000 people but could grow to more than 20 platforms. Picture: Oceanix

Formed entirely of massive white hexagonal platforms floating together off the coast of the Korean city of Busan, Oceanix, a planned collection of eco-homes, shops, offices and public spaces, bills itself as the city of the future.

Unveiled amid much fanfare in the UN headquarters in New York, US, in April 2022, the sleek computer-generated images show a series of bio-rock cells each designed to include energy and waste storage as well as agriculture and fish farming.

Designed somewhat like an above-water version of the Octopod from the children’s TV series Octonauts, the project has been designed to accommodate 12,000 residents and visitors on three interconnected platforms covering 6.3 hectares. Ultimately it could be expanded to more than 20 platforms accommodating 100,000 people.

Oceanix, a company founded by Marc Collins Chen, a former minister of tourism for French Polynesia, and former United Nations official Itai Madamombe, says the initial stage of the project will be completed by 2025 at a cost of US$200 million, in time to form part of Busan’s bid to host World Expo 2030.

Backed by the United Nations’ sustainable development arm, UN Habitat, and Busan Metropolitan City, Oceanix forms a prototype including aeroponic farming (the process of growing plants with only water and nutrients), water harvesting and pedestrian-only walkways, which the company hopes to replicate at scale off coastal cities all over the world.

“Today’s diverse urban areas face new and growing threats – not least from climate change and growing inequality,” says UN deputy secretary general Amina Mohammed. “Floating cities can be part of our arsenal of tools.”

What will be in a futuristic city?

“Our approaches to development and environmental sustainability in cities need a serious retooling to meet the challenges of today and tomorrow,” she says. “We live in a time when we cannot continue building cities the way New York or Nairobi were built.

“We must build cities with solutions for low emission development — scaling safe and electric powered public transport solutions and changing the grid on which cities rely to clean energy solutions. We must build cities for people, not cars. And we must build cities knowing that they will be on the frontlines of climate-related risks — from rising sea levels to storms.”

Certainly, the combined problems of a rapidly growing world population coupled with increasing pressure to cut carbon emissions and a willingness to reimagine post-pandemic lifestyles is prompting politicians, NGOs and architects to think carefully about how we live, work, consume and move about in cities, many of which will require similarly radical solutions from those building them.

The United Nations predicts that the global population will increase from around 7.8 billion people today to 9.7 billion in 2050 and could peak at nearly 11 billion in 2100.

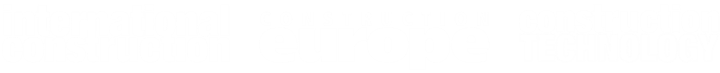

The United Nations predicts that Africa’s urban population will grow dramatically. Source: UN.

The United Nations predicts that Africa’s urban population will grow dramatically. Source: UN.

Most of this growth is expected to take place in cities. Today, 55% of the world’s population lives in urban areas – with much of this number coming from those in the developed world. The percentage of those living in urban areas is expected to increase to 68% by 2050, according to the UN, accounting for another 2.5 billion people.

The problem of packing more and more people into ever larger metropolises is not a new one. For example, over the past two centuries, the population of New York City has increased from just over 100,000 in 1820 to hit more than 5 million by 1920 and by 2020 stood around 8.8 million. More dramatically, the population of Mexico City has risen from 3.3m in 1950 to more than 21 million by 2020.

What is the World’s biggest city?

In order to accommodate their spiralling populations, modern cities have initially grown outwards and then upwards. New York City, the largest city in the world by area, covers a total of 12,093 square kilometers (4,669 square miles) and is currently also home to around 300 skyscrapers – buildings more than 150 meters tall.

If current trends continue, the urban centres of the twenty-first century will be very different from the mega-cities of today.

Over the last century, cities have grown dramatically. Back in 1950, New York City was the world’s largest metropolis with a population of 7.9 million people. It was followed by Chicago, Illinois, with a population of 3.6 million. Today Tokyo in Japan is considered to be the world’s largest city, with a population of around 37 million. Second on the list is Delhi in India, with a population of approximately 32 million.

Researchers predict that by 2100, the world will be home to a new group of ultra-mega cities, many of which will be in Sub-Saharan Africa, with populations of more than double today’s biggest.

According to the World Cities Institute, by 2100 Lagos in Nigeria will be the world’s biggest city with a population of 88.3 million, up from an estimated population of around 20 million today. Kinshasa in Democratic Republic of Congo is expected to grow from 17 million people today, to reach a population of 83.5 million, making it the second largest.

Africa’s population is growing faster than that of any other continent and Africans are moving to cities faster than people elsewhere – especially those south of the Sahara. The World Bank predicts that, by 2100, 13 of the world’s biggest urban areas will be located in Africa, up from just two today.

With rapid growth comes major opportunities. Already growing by thousands of new residents each year, many African cities are home to hundreds of square miles of sprawling slums and informal dwellings, usually built without paved roads, sewerage connections, drinking water and other services. The opportunities for OEMs, contractors and material producers in Africa is huge.

The World Bank estimates that currently 60% of urban dwellers in Africa live in informal and unplanned settlements. The UN says that around 40% of the urban population in sub-Saharan Africa do not have access to electricity.

World’s fastest growing cities

The Makoko community in Lagos. Source: Reuters

The Makoko community in Lagos. Source: Reuters

“Growing cities require substantial investment in infrastructure if they are to continue expanding at their present rate,” says Daniel Dowling, partner at PwC. “We’ve estimated that we will invest US$78 trillion in global infrastructure over the next 10 years alone to accommodate this growth.

“New York, Beijing, Shanghai and London will need US$8 trillion in infrastructure investment alone and it is arguable that the deficit in sub-Saharan Africa is unknown and underestimated, and funding this infrastructure can be a real headache for national and local governments,” he adds.

For city officials grappling with the manifold difficulties of managing largely undocumented urban populations amid political instability this may be easier said than done. Mckinsey estimates that currently 80% of proposed infrastructure projects in Africa never make it beyond the planning stage and only 10% get the required funding to proceed.

Nonetheless, spending on major infrastructure projects is increasing. Deloitte estimates that spending on major projects reached US$521 billion across the continent in 2021 – almost $300 billion more than it recorded in 2013.

A key part of the increase in mega projects taking shape in Africa can be put down to the Chinese government’s aggressive Belt and Road Initiative, which has resulted in billions of dollars of Chinese money (and debt) flooding in to finance major initiatives that are commonly awarded to Chinese contractors.

Yet experts worry that replicating our current model of urban growth is not sustainable. Urban sprawl results in traffic congestion and an over-reliance on cars as well as promoting levels of inequality.

High rise buildings, while creating higher levels of urban density, contain huge amounts of embodied carbon in the concrete and steel required to build them.

Today’s cities are major contributors to climate change. According to UN Habitat, cities consume 78% of the world’s energy and produce more than 60% of the greenhouse gas emissions yet account for less than 2% of the Earth’s surface.

Urban authorities are starting to restrict the growth of some tall steel-framed buildings for safety reasons and as a result of their high carbon footprint. Environmentally-conscious architects around the world have long been calling for all-glass skyscrapers to be banned because they are too expensive to cool.

Skidmore Owings & Merrill has designed “Urban Sequoias” which it claims could remove 1,000 tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere each year. Picture: SOM

Skidmore Owings & Merrill has designed “Urban Sequoias” which it claims could remove 1,000 tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere each year. Picture: SOM

Are skyscrapers evolving?

In 2019, then New York Mayor Bill de Blasio promised to introduce legislation to the city introducing new energy code requirements as a prerequisite for building permits, which he said would make it harder to create energy-consuming glass and steel structures.

And in 2021, the Chinese government passed a new law restricting smaller cities across the country from building super skyscrapers of more than 250m and strictly limiting the construction of those of more than 150m as part of a crackdown on “vanity projects” and to reduce energy consumption.

Instead, experts say that they expect architects and construction teams to harness the powers of new technology such as Building Information Modelling (BIM) and off-site construction.

“Crucially, technology can help make projects faster, a key benefit in an industry with skills shortages and high demand for new development,” says James Chambers, the regional director of US-headquartered software company Bluebeam.

“Massive strides are being made in terms of new building materials and methods, such as smart concrete, engineered timber and 3D printed structures,” he adds. “There is also increasing use of offsite, ranging from pre-assembled components through to full modular solutions.”

One way in which architects are trying to construct sustainable high-rise buildings is through the use of towers built from mass timber products – sometimes jokingly known as ‘plyscrapers’.

They are made by gluing dried strips of laminated wood together at 90-degree angels and compressing them under pressure to produce a substance that its engineers say outperforms steel and concrete in terms of strength, fire resistance and sustainability. The world’s tallest wooden building, Mjøstårnet was completed in the Norwegian town of Brumanunddal on behalf of developer AB Invest in 2019 by Norwegian contractor Hent.

How to make cities sustainable

The Mjøstårnet tower in Brumanunddal, Norway, is the world’s tallest wooden building. Photo: Moelven

The Mjøstårnet tower in Brumanunddal, Norway, is the world’s tallest wooden building. Photo: Moelven

Since then, more wooden towers have been completed including the 24-storey HoHo Vienna in Austria and the 19-storey Terrance House in Canada, as well as the 25 storey Ascent tower that is currently under construction in Wisconsin, US.

“It’s really inspiring to see the massive interest for this building worldwide,” says Rune Abrahamsen, CEO of Moelven Limtre, the turnkey subcontractor on the project that supplied the CLT (Cross-laminated timber). “There are great demands for sustainable solutions in the future and Mjøstårnet is now the world’s tallest showcase for just that.”

Chicago-based architecture firm Skidmore Owings & Merrill goes further. At last year’s COP 26 it unveiled plans to create high-rise buildings constructed using carbon-absorbing materials, containing plants and algae and designed to create a ‘stack effect’ that would absorb carbon from the air.

Dubbed ‘Urban Sequoias,’ it boasts that these towers, none of which have yet been constructed, would each be able to remove up to 1,000 tonnes of carbon from the atmosphere every year.

“This solution allows us to move beyond net zero to deliver carbon absorbing buildings, increasing the amount of carbon removed from the atmosphere over time,” says Kent Jackson, a partner at SOM.

“After 60 years, the prototype would absorb up to 400% more carbon than it could have emitted during construction.”

Why 3D printing could be the future

Prefabricated buildings have been used in construction for more than a century. However, advances in technology, especially in the field of 3D printing, mean that it is possible for builders to create components or even full housing units, often in the space of just a few hours by far fewer people than would typically be necessary.

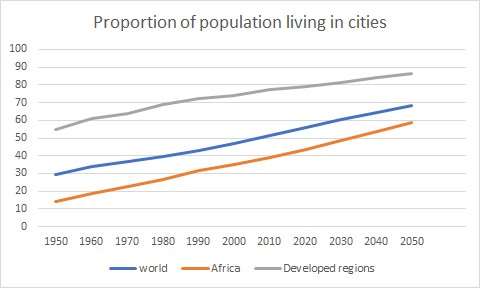

Holicm claims its 14Trees joint venture has created Africa’s first 3D printed house. Photo: 14Trees

Holicm claims its 14Trees joint venture has created Africa’s first 3D printed house. Photo: 14Trees

Although still in its infancy, 3D printing technology is evolving rapidly with manufacturers in China, Dubai, the US and Europe all printing housing and office pods that they claim to be prototypes for the future.

Last year, cement manufacturer Holcim announced that it had signed an agreement to build a 52-unit affordable housing project in Kenya, which it claims is Africa’s largest to date as part of its 14Trees joint venture. Holcim said that it had improved its technology, enabling it to create load-bearing walls and giving them structural function.

The Dubai Municipality has even promised that by 2030, around a quarter of all new buildings will be made using the technology.

Developers say that the process, which normally entails a giant robotic arm smearing layers of cement, limestone or even recycled glass with a binder on top of each other and then leaving the resulting structure to harden, could be a game changer for providing functional affordable housing in fast growing areas.

NASA has even announced plans to use 3D printing to construct buildings on the Moon using lunar soil.

“With today’s rapid urbanisation over three billion people are expected to need affordable housing by 2030. This issue is most acute in Africa, with countries like Kenya already facing an estimated shortage of two million homes,” says Jan Jenisch, CEO of Holcim.

“By deploying 3D printing we can address this infrastructure gap at scale to increase living standards for all.”

Whether 3D printing is the answer – or even part of the answer – in the future is currently unknown. What is known is that the geographical areas of where the world’s biggest cities are located will change, as will the buildings located within them. Both these facts provide a real opportunity for those in the construction industry.

STAY CONNECTED

Receive the information you need when you need it through our world-leading magazines, newsletters and daily briefings.

CONNECT WITH THE TEAM